The Inside Scoop on Seattle's Gig Work Wage Laws

Policy crafters Kerem Levitas and Tina Sigurdson share how rideshare, delivery laws came about

Few cities have been at the forefront of regulating the gig work and app economy as much as Seattle. In 2020, the city passed “Fare Share,” setting up a new compensation system for rideshare drivers; two years later it followed up with PayUp, which regulates the food delivery ecosystem. While at first glance the two policies share fundamental aims, the laws were crafted by different teams responding to different stakeholders.

As we see cities like Minneapolis and NYC working on their own new rules to regulate gig work, I thought to reach out to the policy experts that crafted Seattle’s laws, so we can learn from their experiences.

Jonah Bliss: Kerem, Tina, it’s great to chat with you both. Let’s start with some context; could you tell us about yourself, what you do, your path towards your current role?

Kerem Levitas: Thanks Jonah. I serve as the Policy Manager at the Office of Labor Standards (OLS) in Seattle, where I’ve worked for about 7 years. I started off working with different businesses and supporting them on compliance work with the different local labor laws in Seattle. About four years ago I transitioned into policy work, with a focus on the gig economy and non-standard work structures. I led the City’s policy efforts to develop minimum wage and deactivation protections for Uber and Lyft drivers, which culminated in what was called the “Fare Share” initiative. Since then I’ve focused on work protections for other sectors of the gig economy. Prior to that I was an attorney in private practice, representing both businesses and workers in employment issues.

Tina: I have been a policy analyst at OLS for a little over a year now. I work on Kerem’s team, helping to implement City labor laws and provide compliance assistance to employers. Before that, I have worked on public policy matters related to gig and other low-wage work, as well as environmental and consumer protection.

Seattle has been at the forefront of regulating the gig economy lately, with both the Pay UP and Fare Share ordinances. Can you explain to our readers what those two laws do?

Fare Share consists of two ordinances. One establishes minimum pay requirements based on a per minute and per mile minimum. These minimums guarantee drivers a living wage for all their working time (including waiting time, sometimes called P1) plus compensation for expenses. It recognizes that if the TNCs don’t pay drivers for waiting time or their expenses, ultimately they will make below minimum wage. The Deactivation Ordinance creates rules to guarantee fair deactivations and create a transparent process for drivers to challenge deactivations. It addresses complaints that drivers have sometimes been deactivated by algorithm for things that may not make sense, and that it was very difficult for workers to get a human to review the issue and correct mistakes. It also recognizes that there are many reasons deactivations are necessary, and provides the flexibility for the companies to deactivate in these situations.

Pay Up: Similar to the TNC minimum pay ordinance, the App-Based Worker Minimum Payment Ordinance requires workers to be paid a minimum wage for their time and compensated for expenses, including mileage—just like all employees under City law. The rates include a small markup for the app-based workers’ time which is not directly compensated but is inherent to the work—for example the time to return from a delivery in an outer neighborhood to a busier area.

The 2024 rates are $0.44 per minute, $0.74 per mile, or a $5 minimum per job. Delivery workers do not make $26.40 per hour as reported in some media outlets. That is the rate they could earn if they had no downtime between orders. In reality, most delivery workers experience significant downtime between orders.

There is also an App-Based Worker Paid Sick and Safe Time Ordinance, so that they can take time off when sick like other workers.

What was the city’s intention with creating the ordinances, who led the process for each, and went into crafting both laws?

Fare Share: The City began to hear from drivers and driver groups about two primary concerns—first, their pay was decreasing such that they had to work longer hours to make ends meet; second, the companies could deactivate them for reasons that didn’t make sense and they had no way to discuss the issue with anyone who could correct sometimes simple mistakes. The City took these concerns seriously and embarked on a very robust research and policy process. We conducted multiple roundtables with driver groups, including groups selected by Uber and Lyft, held randomly selected focus groups, and conducted a telephone town hall with over 8,900 participants. Further, we conducted a quantitative analysis working with two academic economists who analyzed driver pay based on some company-provided data, and data from a survey fielded to over 30,000 licenses drivers. Echoing the anecdotal concerns we initially heard, this research yielded two results: first, drivers earned an average of $9.73 per hour (after accounting for expenses)—far below Seattle’s minimum wage—and, second, deactivations were a major concern.

Pay Up: For years, network companies have paid gig workers, who are disproportionately immigrants and people of color, subminimum wages. Workers reported that on some delivery offers, they would net zero income after expenses. On many others, they would earn just a few dollars—far below Seattle’s minimum wage. Seattle’s policies for app-based workers recognize that app-based workers fuel our city’s economy and deserve fair wages like all other workers so they can live and succeed in Seattle.

Moreover, delivery workers put themselves at risk during the pandemic to ensure that others could shelter in place. The City thought it was important that they have a living wage and can take time off when sick for public health reasons.

The app-based worker ordinances were developed through a stakeholder process that was managed by members of City Council. Therefore, OLS (an office within the executive branch of the City) participated but did not lead the process like during development of Fare Share. It’s also worth noting that although restaurant delivery work has received the most public attention, the “Pay Up” policies cover a much broader group of workers than Fare Share. This also made the policy development process inherently different than processes for a more narrowly applied set of policies.

Seattle in general has very progressive laws around minimum wage, $19.97 an hour for large employers. Was the thought with these gig pay laws to essentially bring contract workers up to the same minimum standards received by employees?

The idea was to take laws that apply to employees around minimum wage, compensation for expenses, and paid sick and safe time and try to create complimentary standards for this workforce. Of course, some modifications were needed due some unique aspects of this sector. Put another way, employees in Seattle must receive minimum wage and compensation for expenses (like the use of a personal vehicle), so the “Pay Up” and Fare Share laws likewise require that workers are paid at least minimum wage and compensated for expenses like gas, insurance, and depreciation. Similarly, employees are allowed to take off paid time when they are sick or to care for a loved one, and Pay Up likewise includes a similar protection.

We’ve understandably seen a lot of pushback from the 3PDs about the new legislation, including a particular claim that the city was perhaps too conservative in its modeling of vehicle depreciation, as it assumed drivers use “vans, pickups, and panel trucks” as opposed to pre-existing sedans. What do you think of that claim, and of how the industry has responded in general?

Yes, we addressed this somewhat above. In Seattle, employees are entitled to Seattle Minimum Wage and reimbursement for expenses incurred by reason of employment (including driving a personal vehicle for work purposes) under our Wage Theft Ordinance, SMC 14.20. The idea in this policy arena is to take those rights and extend them to the gig sector, with some modifications for the unique nature of the work. As to the specific mileage reimbursement number, in “Pay Up” that is based on the IRS rate for vehicle deductions. The number is almost universally accepted across industries as the correct rate to reimburse workers for use of a personal vehicle for work purposes. Quite literally, it is the rate at which my current employer and all of my previous employers reimbursed me when I drove my own car for work, even though I own a sedan and not a “van, pickup, or panel truck.” The IRS does not disclose the fleet makeup they use to determine the rate, so it’s impossible to know how big a factor those vehicles are. But other models that do not include those vehicles—including Seattle’s own TNC rate study—have resulted in fairly similar per mile rates. (See Seattle TNC study; NYC TNC rates; Minnesota TNC rate study; AAA real costs of ownership)

Given that Fare Share happened in 2020, and Pay Up in 2022, what’s changed since at the local or state wide level?

Fare Share: In 2022, the Washington State Legislature passed a statewide pay standard (as well as other protections) for TNCs like Uber and Lyft. Since that point, the City no longer regulates these issues.

For Pay Up, the City is currently in the process of establishing rules for data production that will enable us to do some of the impact assessment discussed above. An ordinance related to deactivation (i.e. kicking a worker off a platform) will go into effect in January 2025.

One thing that I think is overlooked a bit about Pay Up is that it isn’t just about food delivery, but about all IC-style gig work in the city. What’s the bigger story there?

Yes, these policies were conceived to apply to most types of app-based work not already covered by Fare Share (i.e., rideshare driving), meaning the ordinances cover more than just food delivery. All kinds of work across a variety of industries are now facilitated via apps, and new companies that bring this technology to longstanding occupations are constantly emerging. For example, apps now facilitate moving, automotive repair, massage therapy, and laundry services, as well as warehouse, hotel, restaurant, and even healthcare staffing, and more. The ordinances cover most services that are physically performed in the city and facilitated by covered companies, ensuring that workers receive some basic protections even when their work is obtained through an app.

Any final thoughts, or advice for other policymakers working in this space?

In any policy making area, it is important to have a balanced approach that centers impacted workers, and equally considers concerns from businesses. Building in data production and analysis is key to understanding impacts. The City is committed to this type of broad based approach and open to iterating and innovating where data shows the initial direction may need refinement. The nature of work is changing rapidly and it’s important for the social contract and workplace protections to evolve with it, in a way that fosters innovation, supports the economy and values the essential labor of all workers. At the end of the day, we all do better when we ALL do better.

HOT INDUSTRY NEWS & GOSSIP

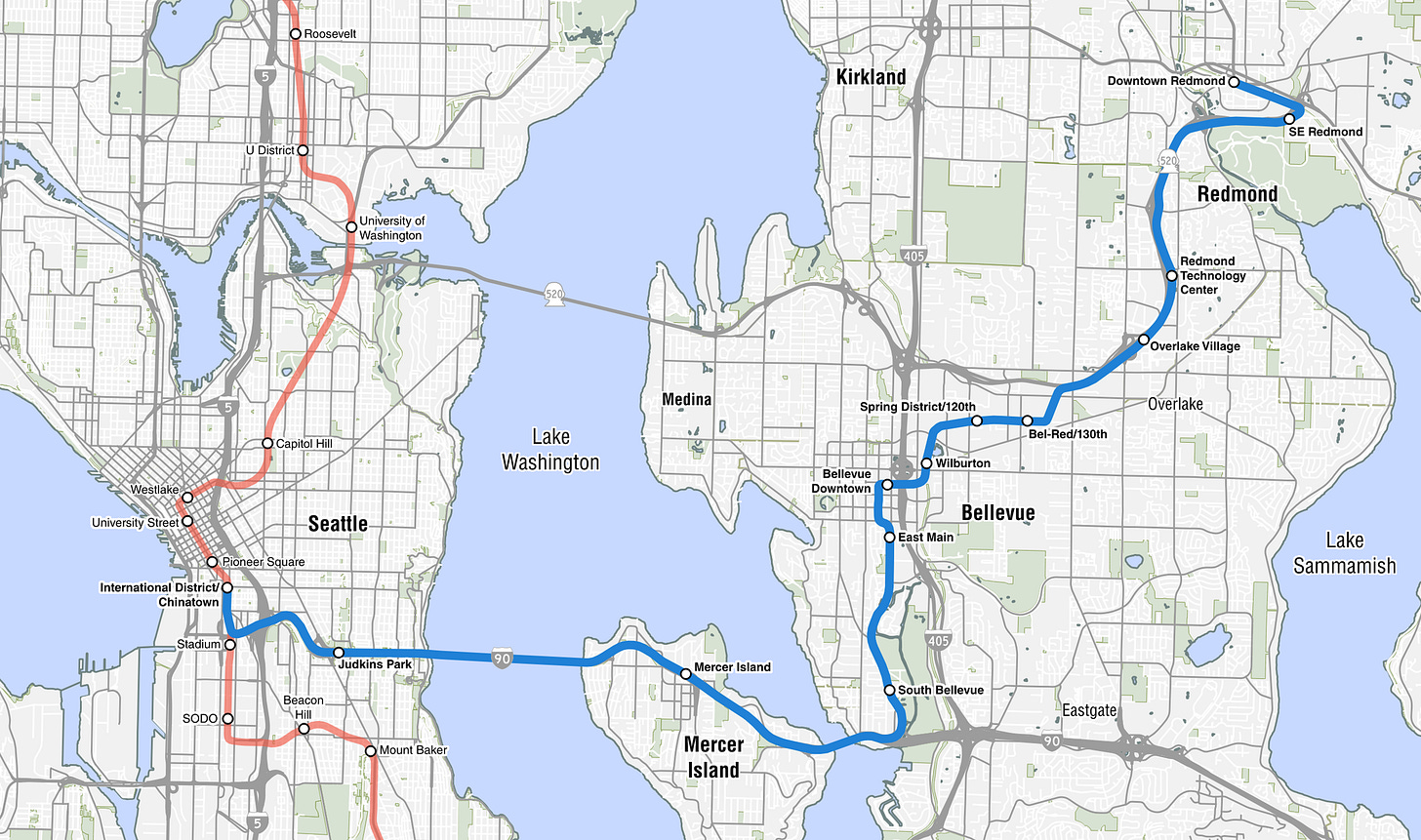

Speaking of Seattle: The Puget Sound region celebrated the opening of the first portion of its new Link 2 Line light rail service. This brings urban rail service to the busy business hubs of Bellevue and Richmond, with an aquatic crossing to Seattle proper scheduled to open next year.

Curbtopia! Friend of the curb Matt Daus maps out the ideal future for city streets, sidewalks and yes: curbs.

So much for reliable electrification: The levelheaded leadership at Tesla took an axe to the entire Supercharger team, dealing a major blow to its continued expansion and integration with additional automakers. One of Tesla’s strongest advantages has been its robust and reliable charging network, so this is not just a blow to the OEM itself, but the whole EV ecosystem.

Getir gets out: Maybe super fast delivery only works in emerging economies? Getir officially pulled the plug on its quick commerce ops in U.S., the U.K. and the E.U., keeping just its Turkish operations alive.

New curb collaborator coalesces: Modaxo completed its acqusition of Conduent’s popular curb management platform, rechristening it as Trellint. Longtime leaders like Jim Vaca and Kirk Strassman are staying in place, working alongside other Modaxo brands like TransLoc and Trapeze.

See you at VerdeXchange 2024: The most dynamic sustainability conference — VerdeXchange — is back in Los Angeles, May 12-15. Check out the can’t miss program, and for our collegiate or recently graduated readers: register to volunteer, it’s a great way to meet the movers and shakers of the green economy!

A few good links: A primer on the policies that have led to America’s bloated auto sizes. Amazon Prime Air heads to Arizona. Shin-pei Tsay named the new Director of Boston’s Office of New Urban Mechanics. Uber Eats delivers results for Domino’s. Worth the gamble: Siemens wins Brightline West train contract. Transit ridership recovery in Canada outpaces America. A very good photo. Populus wins Hoboken contract. In case you missed it: videos from Curbivore 2024 now available.

Until next week!

- Jonah Bliss & The Curbivore Crew